Abstract

The Zambian government stated that the country should become a prosperous middle-income nation by 2030. For this to be achieved strong organizations that create a strong economy are needed. The purpose of this study was to evaluate whether the high performance organization (HPO) Framework, which was developed based on data collected worldwide, could be applied in the Zambian context to help strengthen and improve Zambian governmental institutions. A mixed method approach was used in which: (a) questionnaires were collected from a Zambian Ministry in order to be able to apply a confirmatory factor analysis to validate the five factors of the HPO Framework; and (b) a workshop was held in which the CFA results were discussed and potential organizational improvements for the Ministry were identified. The study validated the HPO Framework in the Zambian context and showed that it can be used to raise the quality of Zambian governmental institutions.

organizations that create a strong economy are needed. The purpose of this study was to evaluate whether the high performance organization (HPO) Framework, which was developed based on data collected worldwide, could be applied in the Zambian context to help strengthen and improve Zambian governmental institutions. A mixed method approach was used in which: (a) questionnaires were collected from a Zambian Ministry in order to be able to apply a confirmatory factor analysis to validate the five factors of the HPO Framework; and (b) a workshop was held in which the CFA results were discussed and potential organizational improvements for the Ministry were identified. The study validated the HPO Framework in the Zambian context and showed that it can be used to raise the quality of Zambian governmental institutions.

Introduction: high performance governmental organizations

In a recent editorial comment in one of Zambia’s biggest national newspaper, Zambia’s work culture was lamented: “Fackson Shamenda, our Minister of Labor, says the poor work culture among Zambians has led to low productivity in most institutions in the country. We agree. Fackson also says that the work culture in the country should change if Zambia is to develop. Again we agree. It’s time for this country to wake up and start taking pride in our work” (The Post, 2012, p.36). The editorial comment ends with a call to action: “Clearly, if our country is to move forward, honest and hard work is demanded of us all. It is said that what a single ant brings to the ant hill is very little; but what a great hill is build when each one does their proper share of the work!” (The Post, 2012, p.36). This call is all the more pressing as the Zambian government, in its long-term development strategy, stated that the country should become a prosperous middle-income nation by 2030: “By 2030, Zambians, aspire to live in a strong and dynamic middle-income industrial nation that provides opportunities for improving the well being of all, embodying values of socioeconomic justice, underpinned by the principles of: (i) gender responsive sustainable development; (ii) democracy; (iii) respect for human rights; (iv) good traditional and family values; (v) positive attitude towards work; (vi) peaceful coexistence and; (vii) private-public partnerships” (Republic of Zambia, 2006, p. vi). To reach this objective, a series of national development plans was developed of which the sixth is covering the years 2011 through 2015.

The question is how these objectives, formulated in the national development plan and the editor’s call for action, can be reached. In this research we evaluate whether the high performance organization (HPO) framework – a framework which contains validated factors that have a strong positive correlation with high organizational performance – could be used for helping the Zambian government achieve its objectives by transforming Zambian governmental agencies into high performing agencies. This article is structured as follows. In the next two sections a literature review of high performance research in the Zambian context and the theoretical framework for the study – the HPO Framework – are given. Subsequently the case organization, the Ministry of Commerce, Trade and Industry, is introduced and the research approach and research results are described. This is followed by the analysis, and the article ends with a conclusion, theoretical and practical implications, limitations of the study, and possibilities for further research.

Literature Review

Research has shown the role of strong organizations in creating a strong economy, needed to become a stable and enduring middle-income nation (Aiginger, 2009; Cheung and Chan, 2012; Ionescu, 2012). Thus it is important that organizations, both private and public ones, should become strong. A method to achieve this is by organizations becoming so-called high performance organizations (HPOs). In the literature many different definitions and descriptions of an HPO can be found, which have several themes in common: an HPO achieves sustained growth, over a long period of time, which is better than the performance of its peer group (Collins and Porras, 1997; Geus, 1997; Brown and Eisenhardt, 1998; Zook and Allen, 2001); an HPO has a great ability to react and adapt to changes (Kotter and Heskett, 1992; Goranson, 1999; Quinn et al., 2000; Weick and Sutcliffe, 2001); an HPO has a long-term orientation (Mische, 2001; Maister, 2005; Miller and Breton-Miller, 2005; Light, 2005); the management processes of a HPO are integrated and the strategy, structure, processes and people are aligned throughout the organization (Hodgetts, 1998; Kirkman et al., 1999; Lee et. al., 1999; O’Reilly and Pfeffer, 2000); and an HPO spends much effort on improving working conditions and development opportunities of its workforce (Kling, 1995; Lawler et al., 1998; Manzoni, 2004; Underwood, 2004; Holbeche, 2005; Siroat et al., 2005).

When looking at research into the characteristics of HPOs in Zambia, it turns out there is a shortage of these type of studies. An overview of 290 studies into high performance and excellence conducted in the period 1960 until 2007 (Waal, 2006, rev. 2010; 2012a) revealed that in none of these studies Zambian organizations were involved. A subsequent search of the academic databases – such as EBSCO, Science Direct and Emerald – into recent literature did not yield comprehensive HPO studies on Zambia either, as most studies found were into aspects (loosely) related to high performance in the Zambian context. Soest (2007) looked at the capability of the Zambia Revenue Authority to raise revenue and identified the process and output dimensions that play a part in this. Burger (2011) investigated the performance difference in schooling attainment rates between urban and rural residents, and found that differences in the presence of resources and in the returns on resources caused the gap in schooling performance. Mwenda and Mutoti (2011) investigated the effects of market-based financial sector reforms on the competitiveness and efficiency of commercial banks and economic growth in Zambia, and found that the reforms had significant positive effects on bank cost efficiency but insignificant effects on macroeconomic variables such as per capita GDP and inflation. Finally, Gow et al. (2012) investigated the relation between the salaries of health workers in Zambia, their satisfaction and motivation, and their performance and found that their low incomes had many negative implications such as high absenteeism, low output, poor quality health care, and the departure of health workers to the private sector and overseas.

Next to this Zambian specific research, studies can be found on larger samples of countries which incorporated Zambia. For instance, Jain (2007) looked at the application of knowledge management by university libraries in eight countries situated in East and Southern Africa, among which Zambia, and found that these libraries mainly practice information management thus not yet realizing the importance of knowledge management as source for competitive advantage. Bolden and Kirk (2009) provided an account of the meanings and connotations of ‘African leadership’ in five African countries, which included Zambia, and found that the notion of the ‘African renaissance’ called for a reengagement with indigenous knowledge and practices. Wanasika et al. (2011) examined the state of managerial leadership in Sub-Saharan Africa countries, that also included Zambia, and found high levels of group solidarity, paternalistic leadership, and Humane Oriented leadership. Allard et al. (2012) investigated the impacts of political instability and pro-business market reforms on national systems of innovation across a range of developing and developed countries – including Zambia – and found evidence suggesting that national systems of innovation are most likely to flourish in developed, politically stable countries and less likely to prosper in historically unstable countries. Mittal and Dorfman (2012) analyzed the degree to which the five aspects of servant leadership (i.e. egalitarianism, moral integrity, empowering, empathy and humility) were important for effective leadership across cultures, among which the Zambian culture, and found that the dimensions were associated with effective leadership, but with a considerable variation in degree of importance. Ngobo and Fouda (2012) explored the link between good governance and profitability of firms in African countries, among which Zambian organizations, and found that good governance reduced the variability of Zambian companies’ profitability which lead to more high-return and low-risk investments. Wu (2012) analyzed data on 19,653 firms from 73 emerging economies, among which Zambia, to examine how a firm’s marketing capabilities affected its performance, and showed that this relationship is systematically moderated by the level of institutional development in the country, i.e. economic conditions, legislative institutions and social values all have an impact. Finally, Wu et al. (2012) examined the effect of countries’ governance environments on their propensity to trade, and found for Zambia a relation-based environment (i.e. a weak rule of law and strong informal networks based on private relations) which caused less trade to take place in this country.

The conclusion of this literature review has to be that no holistic and scientifically validated framework of what constitutes a high performing Zambian organization – profit nor non-profit nor governmental – has thus far been developed and described in the literature. Thus we have to turn to generic HPO Frameworks. Many of these have been developed based on data from Western countries, mainly the USA. This is illustrated by looking at the percentage of studies in the aforementioned overview of 290 studies into high performance and excellence (Waal, 2006, rev. 2010) which include US organizations, which is 33.8 percent. So many of the HPO frameworks developed in these studies have a strong Western focus which means they cannot be implemented indiscriminately in other cultural contexts, such as in Zambia. After all, previous research on the application of techniques developed in the West in other cultural settings has shown that these techniques often do not work well (Branine and Pollard, 2010; Elbanna and Gherib, 2012; Hempel, 2001; Holtbrügge, 2013; Manwa and Manwa, 2007; Matiċ, 2008; Palrecha, 2009; Rees-Caldwell and Pinnington, 2013; Wang, 2010). In addition, there is often inconclusive proof on whether importing Western management practices into organizations in non-Western countries indeed improves performance (Al-Husan et al., 2009). At the same time research on globalization increasingly finds that the transfer of management techniques from one country to another is leading to similar patterns of behavior across these countries (Bowman et al., 2000; Costigan et al., 2005; Deshpandé et al., 2000; Stede, 2003; Zagersek et al., 2004). Thus it is unclear whether applying Western techniques in countries like Zambia is the best route toward sustainable improvement.

A way forward might be to use a framework that has not been developed specifically for one country (neither Western or otherwise) but that can be validated for a specific country like Zambia. Such a framework is offered by Waal (2012) who introduced an HPO Framework, consisting of five factors and 35 underlying characteristics, which was developed based on data collected worldwide, both in developed and developing countries including many African countries. As the HPO Framework has thus far been applied in three African countries – Tanzania (Waal and Chachage, 2011), Rwanda (Waal, 2012b) and South Africa (Waal, 2012b) – it was considered that it might be also applicable in the Zambian context. However, the question remains whether this HPO Framework is valid in the Zambian context. Therefore, the research question of this study is: Can the HPO Framework be applied in the Zambian context? This research question is particular interesting for the governmental sector because Plessis and Plessis (2006) found that the poor quality of governmental institutions in Zambia played an important role in Zambia’s economic decline. This, if governmental institutions would be able to improve and this eventually become high performance governmental organizations, the Zambian economy would benefit considerably. Providing an answer to the research question thus will not only fill a gap in the literature but will also have a practical contribution in that the HPO Framework could potentially be used to raise the quality of the Zambian governmental sector.

Theoretical framework: the HPO Framework

The HPOs Framework was developed based on a descriptive literature review (Phase 1) and empirical study in the form of a worldwide questionnaire (Phase 2) (Waal, 2006 rev. 2010, 2012a, 2012b). The first phase of the study consisted of collecting the studies on high performance and excellence that were to be included in the empirical study. Criteria for including studies in the research were that the study: (1) was aimed specifically at identifying HPO factors or best practices; (2) consisted of either a survey with a sufficient large number of respondents, so that its results could be assumed to be (fairly) generic, or of in-depth case studies of several companies so the results were at least valid for more than one organization; (3) employed triangulation by using more than one research method; and (4) included written documentation containing an account and justification of the research method, research approach and selection of the research population, a well-described analysis, and retraceable results and conclusions allowing assessment of the quality of the research method. The literature search yielded 290 studies which satisfied all or some of the four criteria. The identification process of the HPO characteristics consisted of a succession of steps. First, elements were extracted from each of the publications that the authors themselves regarded as essential for high performance. These elements were then entered in a matrix which listed all the factors included in the framework. Because different authors used different terminologies in their publications, similar elements were placed in groups under a factor and each group – later to be named ‘characteristic’- was given an appropriate description. Subsequently, a matrix was constructed for each factor listing a number of characteristics. A total of 189 characteristics were identified. After that, the ‘weighted importance’, i.e. the number of times a characteristic occurred in the individual study categories, was calculated for each of the characteristics. Finally, the characteristics with a weighted importance of at least six percent were chosen as the HPO characteristics that potentially make up a HPO, this were 35 characteristics.

In Phase 2 the 35 potential HPO characteristics were included in a questionnaire which was administered during lectures and workshops given to managers by the author and his colleagues all over the world. The respondents of the questionnaire were asked to indicate how well their organization performed on the various HPO characteristics on a scale of 1 (very poor) to 10 (excellent) and also how its organizational results compared with its peer group’s. Two types of competitive performance were established (Matear et al., 2004): (1) Relative Performance (RP) versus competitors: RP = 1 – ([RPT – RPW] / [RPT]), in which RPT = total number of competitors and RPW = number of competitors with worse performance; (2) Historic Performance (HP) of the past five years (possible answers: worse, the same, or better). These subjective measures of organizational performance are accepted indicators of real performance (Dawes, 1999; Heap and Bolton, 2004; Jing and Avery, 2008). The questionnaire yielded 2015 responses of 1470 organizations. With a non parametric Mann-Whitney test 35 characteristics, categorized in five factors, with both a significant and a strong correlation with organizational performance were extracted and identified. The factor scales showed acceptable reliability (Hair et al., 1998) with Cronbach alpha values close to or above 0.60.

The research yielded the following definition of an HPO: “an organization that achieves financial and non-financial results that are exceedingly better than those of its peer group over a period of time of five years or more, by focusing in a disciplined way on that what really matters to the organization.” The five HPO factors are:

- Continuous Improvement and Renewal (CI). An HPO compensates for dying strategies by renewing them and making them unique. The organization continuously improves, simplifies and aligns its processes and innovates its products and services, creating new sources of competitive advantage to respond to market developments. Furthermore, the HPO manages its core competences efficiently, and sources out non-core competences.

- Openness and Action-Orientation (OAO). An HPO has an open culture, which means that management values the opinions of employees and involves them in important organizational processes. Making mistakes is allowed and is regarded as an opportunity to learn. Employees spend a lot of time on dialogue, knowledge exchange, and learning, to develop new ideas aimed at increasing their performance and make the organization performance-driven. Managers are personally involved in experimenting thereby fostering an environment of change in the organization.

- Management Quality (MQ). Belief and trust in others and fair treatment are encouraged in an HPO. Managers are trustworthy, live with integrity, show commitment, enthusiasm, and respect, and have a decisive, action-focused decision-making style. Management holds people accountable for their results by maintaining clear accountability for performance. Values and strategy are communicated throughout the organization, so everyone knows and embraces these.

- Long-Term Orientation (LTO). An HPO grows through partnerships with suppliers and customers, so long-term commitment is extended to all stakeholders. Vacancies are filled by high-potential internal candidates first, and people are encouraged to become leaders. An HPO creates a safe and secure workplace (both physical and mental), and dismisses employees only as a last resort.

- Workforce Quality (WQ). An HPO assembles and recruits a diverse and complementary management team and workforce with maximum work flexibility. The workforce is trained to be resilient and flexible. They are encouraged to develop their skills to accomplish extraordinary results and are held responsible for their performance, as a result of which creativity is increased, leading to better results.

An organization can evaluate its HPO status by having its management and employees fill in the HPO Questionnaire, consisting of questions based on the 35 HPO characteristics with possible answers on an absolute scale of 1 (very poor at this characteristic) to 10 (excellent on this characteristic), and then calculating the average scores on the HPO factors. These average scores indicate where the organization has to take action to improve in order to become an HPO. As the five HPO factors have been developed on a dataset consisting of respondents originating from many countries, we can now start validating them for specific countries, such as Zambia.

The Present Study of high performance governmental organizations in Zambia

Setting and Sample

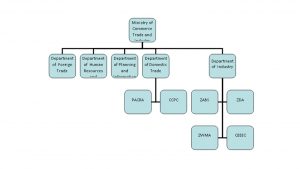

The Ministry of Commerce, Trade and Industry (MCTI) is a Government institution charged with the responsibility of formulating and administering policies and regulating activities in the trade and industrial sectors. The goal of MCTI is to enhance the sectors’ contribution to sustainable social economic growth and development, for the benefit of the people of Zambia. The Ministry is responsible for the following portfolio functions as contained in Government Gazette Notice Number 183 of 2012: investment promotion, trade licensing, privatization, industrial development, companies and business names, industrial research; patents, trademarks and designs; weights and measures; competition and fair trading; small and medium scale enterprises (SMEs) development; and standardization, standards and quality assurance. In addition to the stated portfolio functions, the Ministry is also responsible for the following statutory bodies and Institutions: Zambia Development Agency (ZDA); Zambia Bureau of Standards (ZABS); Competition and Consumer Protection Commission (CCPC); Zambia Weights and Measures Agency (ZWMA); Patents and Companies Registration Agency (PACRA); and the Citizens Economic Empowerment Commission (CEEC). The Ministry also oversees the Competition Protection Tribunal, the Zambia Institute of Marketing, the Zambia International Trade Fair, and the Mukuba Hotel. The Ministry appoints the Boards of the above institutions, with exception of the Citizen Economic Empowerment Commission which is appointed by the President on the recommendation of the Minister. The Zambia Institute of Marketing is an independent institution but draws its mandate through the Minister responsible for commerce. The organizational structure of MCTI is presented in Figure 1.

At the time of research the total number of staff members for all the departments was 404, with another 213 vacancies giving a full establishment of 617, as shown in Table 1. The high number of vacancies is attributed to the high rate of staff turnover which is mainly due to lack of incentives to motivate and retain member of staff (MCTI, 2011). The result of this situation is that MCTI has continued to lose expertise as well as institutional memory.

Research methods

The research into the suitability of the HPO Framework for Zambian governmental institutions organizations can be characterized as being exploratory in nature. In November and December 2012 the HPO Questionnaire was distributed, via the internet, to all managers and employees of MCTI and the four statutory bodies under MCTI. In total 171 (out of 404) completed questionnaires were received which constituted a response rate of 42.3% This data was analyzed using a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), in order to evaluate whether the factors of the HPO Framework were applicable for MCTI. Subsequently, a workshop was organized in Lusaka with representatives of all departments of MCTI and the four statutory bodies. In the next section the results of the data analysis, the HPO Questionnaire, and the workshop are given.

Data Analysis

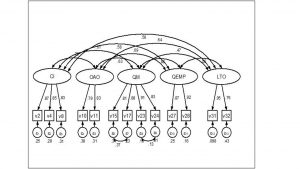

A confirmatory factor analysis was employed to check whether the data in our sample follow the structure of the HPO Framework of Waal (2012a) with 35 items grouped in five factors Continuous Improvement and Renewal (CI), Openness and Action-Orientation (OAO), Management Quality (QM), Long-Term Orientation (LTO) and Workforce Quality (QEMP). In a sequence of steps 13 out of the original 35 items have been retained. The other 22 items were dropped because of high uniqueness or because of high loadings on a mixture of latent variables as indicated by the modification indices. The final model in Figure 2 shows that the loadings of the five dimensions on the retained items are high (in the range of 0.76 to 0.92). The goodness-of-fit statistics are acceptable to good according to the guidelines summarized by Hooper et al. (2008). The RMSEA is 0.076 which is higher than the strict upper limit of 0.07 proposed by Steiger (2007) but a good fit according to traditional measures (MacCallum et al, 1996); the SRMS (0.033) was below 0.05 indicating a good fit (Byrne, 1998); and the CFI of 0.967 is higher than the 0.95 suggested as the benchmark by Hu and Bentler (1999). In terms of discriminant validity the covariances between the five HPO dimensions should be low, but as indicated in Figure 2 two correlations (between QM and QEMP, and between CI and OAO) are high (0.88 and 0.76, respectively); all other correlations between the HPO factors are moderately high, in the 0.47 to 0.69 range.

Figure 2: Results of the confirmatory factor analysis for MCTI

Figure 2: Results of the confirmatory factor analysis for MCTI

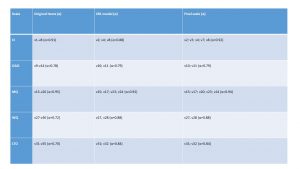

For each of the five scales, Cronbach’s α was computed, both for the original set of all items linked to that scale and for the smaller number of items in the final factor analyzed model. On the basis of item-test correlations, and after cross-checking with the reasons for dropping the items in the sequence of steps in the confirmatory factor analysis, a decision was made on the final scales. Table 2 summarizes the final HPO scales for MCTI, which in total consist of 16 items (compared to the original 35 items).

Table 2: The final HPO scales for MCTI

The results depicted in Figure 2 and Table 2 show that the HPO Framework is valid for MCTI and thus for the biggest governmental institution in Zambia. The data yielded, with a high reliability, the same five HPO factors as in the original HPO Framework, however with a slightly different set of characteristics (16 instead of the original 35). The items that were dropped from the HPO scales of MCTI can be explained from the fact that the original HPO scales were developed on the basis of worldwide collected data (from 50 countries, encompassing both profit, nonprofit and governmental organizations) and thus tailoring to the particular MCTI context had to take place. For further research on the case of the Zambian government we will make use of the scales on the five factors composed of the items indicated in Table 2. In the recommendations and areas of the improvement that follow, we will emphasize only those items that validly and reliably measure these five factors. However, for comparing MCTI to other institutions, we have conveniently stuck to the full 35 item HPO model used in the global data set on HPO.

HPO Questionnaire

The average scores for the five HPO scores were calculated from the completed questionnaires. Also the scores for Zambia organizations and African governmental institutions, which were presented in the database of the HPO Center, are given.

As can be seen from Figure 3, the average HPO score for MCTI makes this organization a well-performing one but not yet an HPO as this requires an average HPO score of at least 8.5 (Waal, 2012b). It is interesting to note the shape of the curves for MCTI, Zambia organizations and African governmental institutions: they are the same. This might mean that employees in African organizations more or less look in the same way at their organization, no matter in which sector it operates: as an organization focused on the longer term, with potentially good management and employees, which need to get better in continuous improvement and should have a better mutual openness.

Workshop

In order to identify the detailed improvement areas for MCTI, in this section the result of the workshop discussions – in which the detailed HPO scores of MCTI were evaluated – are summarized.

Area of improvement 1: Improve the improvement process itself

This area of improvement refers to MCTI having difficulty with improving, simplifying and aligning its processes (HPO characteristics 2, 3 and 4; scores: 6.1, 5.5 and 5.5). Specifically the performance management process has to be addressed (characteristics 5 and 6, scores: 5.9 and 3.8). As reason for these scores were given that there were too many projects with too few people and limited resources, and that departments were understaffed so it was difficult to realize process improvements successfully (the understaffing was already depicted in Table 1). For the performance management process it was put forward that there existed quite a few communication gaps between the various parts of the Ministry and the statutory bodies, causing a poor exchange of information and difficult hand-overs in the process. In addition, there were high levels of controlled information going from top to bottom – caused by the structuring and controlling as predescribed by the Act of Parliament CAP 412. In addition, financial reports were restricted to only a few people, and there was a wide-felt lack of urgency among managers to share information with employees or with each other. Improvements suggested were trying to reform the law and the regulations to be able to share more information and to more easily cooperate, improve and encourage IT usage and innovations, develop an organization-wide management information system, and institute an open door policy. In addition, it was put forward that management should infuse a greater awareness in the institute about the value of sharing information for attaining the HPO status, make selected reports available to selected employees through an intranet, more clearly define the scope of work, strive for more simplifying processes and procedures before adding new ones, and improve funding to departments. A final idea put forth was that all processes of MCTI should be aimed at encouraging raising quality in Zambian society.

Area of improvement 2: Involve employees more, amongst others by sharing more knowledge in the organization

This area of improvement refers to management not involving employees in important processes enough (HPO characteristic 11, score 5.8) and employees themselves only marginally engaging with each other (characteristic 10, score 4.8) enough. There are several reasons for the relatively low scores. As reason for these scores were given that there mainly existed one-way communication due to the nature of the organization which is procedural and works according to protocols which prescribes one-way top-down communication. It was put forward, however, that dialogue occurred within the top management team. Improvements suggested were to let everybody know the value of dialogue for achieving the HPO status, identify channels and opportunities for facilitating dialogue (e.g. round table meetings, informal meetings, management by walking around), and create easier and, simpler communication mechanisms which increase for employees the ease of getting access to management, work toward a change in the mindset of managers of believing that information is power, and encourage more interaction between key players in the organization. It was also suggested that managers, after a dialogue with employees, should visibly issue a plan 2.0 version so employees could see the effect of the dialogue.

Area of improvement 3: make the organization more performance-driven

This area of improvement refers to managers not inspiring employees enough to accomplish extraordinary results, needed for MCTI to become an HPO (HPO characteristic 27; score 6.4). As reason for these scores were given that there were was a lack of key performance indicators (KPIs) on every level in the organization, in general a poor work culture within the civil service, the bureaucracy in the Ministry, and a lack of flexibility in terms of structuring, planning and design of work programs. Possible improvements were that management should let employees see how the collective output is linked to individual performance, involve employees in development and implementation of KPIs, attaching consequences (both positive and negative) on KPI results, implement an Employee Of The Month award for high performers, relax the rules to create more flexibility and adaptability to changing circumstances, empower managers by giving them the authority to make decisions quicker, and letting employees know who the decision-makers are. To inspire enthusiasm for a performance-driven culture is was put forward that the Ministry should have the ambition to become the best ministry in Africa. Another reason for poor performance was said to be a lack of motivation. Employees were not promoted from within the organization, especially at senior management level. Possible area for improvement was that managers should be promoted within MCTI and its statutory bodies and this promotion should be linked to individual performance.

Area of Improvement 4: Decrease staff turnover

This area of improvement refers to high rate of staff turnover, a situation which has lead to inadequate staffing resulting in the inability of MCTI and its statutory bodies to effectively execute programs (HPO characteristics 34 and 35; scores: 4.1 and 5.3). In addition, the organizational structure was said to be inadequate to meet the increased mandate of MCTI. As a result of high number of vacancies and inadequate organizational structure, managers were overworked and therefore achieved insufficient progression. Recommendations were that vacant positions had be filled and the organizational structure should be appropriate and adequately resourced. This would make MCT more responsive to the increased mandate. To address the high rate of turnover of staff it was recommended that MCTI developed and implemented an internal incentive scheme as well as improving the general staff welfare conditions.

Conclusion, limitations and future research

The purpose of this article was to explore the following question: Can the HPO Framework be applied in the Zambian context? With an affirmative answer the framework could support Zambian governmental managers in their efforts to create higher quality governmental institutions which could cope with the challenges set out in Vision 2030. The answer to this question also indicates whether current management and business theories are relevant to the African context, and as such it could contribute to the advancement of management and business in Africa.

The results of the research shows that the five factors of the HPO Framework, based on the outcomes of the CFA, are valid for the Zambian context, although with some contextualization. These can be found in the number of HPO characteristics (16 instead of the original 35) and can be explained by the influence of the Zambian culture and by the fact that the dataset from which the original HPO Framework was derived consisted of respondents from many different cultures. The workshop, were the detailed scores of the HPO Diagnosis at MCTI were discussed, showed that the HPO Framework was positively received by managers and employees from MCTI. They stated that they not only understood the HPO Framework but were also positive about the possibility of using the framework to improve the performance of governmental institutions. The research described in this paper has a theoretical contribution by being the first research into the high performance concept in the Zambian governmental sector, taking into account the influence of the Zambian context. The research addressed many of the concerns associated with study contextualization, as raised by Rousseau and Fried (2001): construct comparability was safeguarded as the meaning and understanding of the HPO factors and characteristics were discussed and verified during the workshop; points of view were multiple and representativeness and levels were the same as both managers and employees of the case company filled in the HPO Questionnaire, just as this happened when collecting the data for the original HPO Framework; range restriction was reflected in the adapted set of 16 characteristics for the Zambian context as compared to the 35 of the original HPO Framework; and time was no issue as the collection of the data for the original HPO Framework and the subsequent confirmatory factor analyses in various countries (including the one for Zambia) was done in the past ten years; and levels. The research also has a practical contribution as the HPO Framework provides Zambian governmental managers with a practical way forward to improve their institutions.

The obvious limitation to the research is that, although MCTI is the largest and arguable the most important ministry of Zambia, it cannot be in advance seen to be representative for all Zambian governmental institutions. Also, although the workshops yielded tangible improvement opportunities, these have not been tested in practice. Thus, further research should focus on getting the views from more Zambia organizations, but governmental and profit, and especially on testing the HPO Framework in practice by implementing the recommendations in MCTI and then tracking the performance of this institution over time. In this way, it can be evaluated if the advantages experienced by organizations while applying the HPO Framework are also enjoyed by a Zambian organization. Future research could also evaluate whether there are differences between Zambian public and Zambian private organizations in applying the HPO Framework. Finally, this research shows the potential of the HPO Framework for Zambian organizations, but it does not discuss specifically how the HPO framework itself caters for the Zambian context. As the HPO Framework is more or less culturally neutral – it points out what should be improved, which is generically valid in many countries, but it does not stipulate how to improve ‘the what’, something which depends on the culture – future research could look into the degree in which the characteristics of the HPO Framework itself are suited to the Zambian context, in comparison to other quality and performance improvement models and frameworks.

By André de Waal, Robert Goedegebuure and Tobias Mulimbika

References

Aiginger, K. (2009), ‘Strengthening the resilience of an economy’, Intereconomics, Vol. 44, Issue 5, 309-316.

Al-Husan, F.Z.B., Brennan, R. and James, P. 2009, ‘Transferring Western HRM practices to developing countries: The case of a privatized utility in Jordan’, Personnel Review, Vol. 38, Issue 2, 104-123.

Allarda, G., Martinez, C.A. and Williams, C. (2012), ‘Political instability, pro-business market reforms and their impacts on national systems of innovation’, Research Policy, Vol. 41, 638– 651.

Bolden, R. and Kirk, P. (2009), ‘African Leadership: Surfacing New Understandings through Leadership Development’, International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, Vol. 9, No. 1, 69–86.

Bowman, D., Farley, J.U. and Schmittlein, D.C. (2000), ‘Cross-national empirical generalization in business services buying behavior’, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 31, No. 4, 667-685.

Branine, M. and Pollard, D. (2010), ‘Human resource management with Islamic management principles’, Personnel Review, Vol. 39, Issue 6, 712-727.

Brown, S.L. and Eisenhardt, K.M. (1998), Competing on the edge. Strategy as structured chaos, Harvard Business School Press, Boston.

Burger, R. (2011), ‘School effectiveness in Zambia: the origins of differences between rural and urban outcomes’, Development Southern Africa, Vol. 28, No. 2, 157-176.

Byrne, B.M. (1998), Structural Equation Modeling with LISREL, PRELIS and IMPLIS: Basic Concepts, Applications and Programming. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

Cheung, H. Y. and Chan, A.W.H. (2012), ‘Increasing the competitive positions of countries through employee training, the competitiveness motive across 33 countries’, International Journal of Manpower, Vol. 33, Issue 2, 144-158.

Collins, J. (2001), Good to great. Why some companies make the leap … and others don’t, Random House, London.

Collins, J.C. and Porras, J.I. (1994), Built to last. Successful habits of visionary companies, Harper Business, New York.

Costigan, R.D., Insinga, R.C., Berman. J.J., Ilter, S.S., Kranas, G. and Kureshov, V.A. (2005), ‘An examination of the relationship of a Western performance-management process to key workplace behaviours in transition economies’, Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, Vol. 22, No. 3, 255-267.

Dawes, J. (1999), ‘The relationship between subjective and objective company performance measures in market orientation research: further empirical evidence’, Marketing Bulletin, Vol. 10, 65-76.

Deshpandé, R., J Farley, J.U. and Webster Jr., F.E. (2000), ‘Triad lessons: generalizing results on high performance firms in five business-to-business markets’, International Journal of Research in Marketing, Vol. 17, 353-362.

Elbanna, S. and Gherib, J. (2012), ‘Miller’s environmental uncertainty scale: an extension to the Arab world’, International Journal of Commerce & Management, Vol. 22, Issue 1, 7-25.

Geus, A. de (1997), The living company. Habits for survival in a turbulent environment, Nicholas Brealey, London.

Goranson, H.T. (1999), The agile virtual enterprise. Cases, metrics and tools, Quorum Books, Westport.

Gow, J., George, G., Mwamba, S., Ingombe, L. and Mutinta, G. (2012), ‘Health Worker Satisfaction and Motivation: An Empirical Study of Incomes, Allowances and Working Conditions in Zambia’, International Journal of Business and Management, Vol. 7, No. 10, 37-48.

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R.E., Tatham, R.L. & Black, W.C. (1998), Multivariate Data Analysis, Prentice-Hall, New Jersey.

Heap, J. and Bolton, M. (2004), ‘Using perceptions of performance to drive business improvement’, In Neely, A., Kennerly, M. and Waters, A. (Eds.), Performance measurement and management: public and private, Centre for Business Performance, Cranfield University, 1085-1090.

Hempel, P.S. (2001), ‘Differences between Chinese and Western managerial views of performance’, Personnel Review, Vol. 30, Issue 1/2, 203-22.

Hodgetts, R.M. (1998), Measures of quality and high performance. Simple tools and lessons learned from America’s most successful corporations, Amacom, New York.

Holbeche, L. (2005), The high performance organization. Creating dynamic stability and sustainable success, Elsevier Butterworth Heinemann, Oxford.

Holtbrügge, D. (2013), ‘Indigenous Management Research’, Management International Review, Vol. 53, Issue 1, 1-11.

Hooper, D., Coughlan, J. and Mullen, M. R. (2008), ‘Structural Equation Modeling: Guidelines for Determining Model Fit’, The Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, Volume 6 Issue 1 2008, pp. 53 – 60

Hu, L.T. and Bentler, P.M. (1999), ‘Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria Versus New Alternatives’, Structural Equation Modeling, 6 (1), 1-55.

Ionescu, L. (2012), ‘Global competitiveness, bureaucracy and the quality of institutions’, Economics, Management & Financial Markets, Vol. 7, Issue 4, 733-740.

Jain, P. (2007), ‘An empirical study of knowledge management in academic libraries in East and Southern Africa’, Library Review, Vol. 56, Issue 5, pp. 377 – 392.

Jing, F.F. and Avery, G.C. (2008), ‘Missing links in understanding the relationship between leadership and organizational performance’, International Business & Economics Research Journal, Vol. 7, Issue 5, 67-78.

Kirkman, B.L., Lowe, K.B. and Young, D.P. (1999), High-performance work organizations. Definitions, practices, and an annotated bibliography, Center for Creative Leadership, Greensboro, N.C.

Kling, J. (1995), ‘High performance work systems and firm performance’. Monthly Labour Review, May, 29-36.

Kotter, J.P. and Heskett, J.L. (1992), Corporate culture and performance, Free Press, New York.

Lawler III, E.E., Mohrman, S.A. and Ledford jr., G.E. (1998), Strategies for high performance organizations, The CEO report,Jossey-Bass Publishers, San Francisco.

Lee, T.H., Shina, S. and Wood, R.C. (1999), Integrated management systems. A practical approach to transforming organizations, John Wiley and Sons, New York.

Light, P.C. (2005), The four pillars of high performance. How robust organizations achieve extraordinary results, McGraw-Hill, New York.

MacCallum, R.C., Browne, M.W., and Sugawara, H., M. (1996), ‘Power Analysis and Determination of Sample Size for Covariance Structure Modeling’, Psychological Methods, 1 (2), 130-49

Maister, D.H. (2001), Practice what you preach. What managers must do to create a high achievement culture, Free Press, New York.

Manwa, H. and Manwa, F. (2007), ‘Applicability of the western concept of mentoring to African organizations: a case study of Zimbabwean organizations’, Journal of African Business, Vol. 8, Issue 1, 31-43.

Manzoni, J.F. 2004. ‘From high performance organizations to an organizational excellence framework’, In: Epstein, M.J. and Manzoni, J.F. (eds.). Performance measurement and management control: superior organizational performance, Studies in managerial and financial accounting, volume 14, Elsevier, Amsterdam.

Matiċ, J.L. (2008), ‘Cultural differences in employee work values and their implications for management’, Management, Vol. 13, No. 2, 93-104.

Miller, D. and Le Breton-Miller, I. (2005), Managing for the long run. Lessons in competitive advantage from great family businesses, Harvard Business School Press, Boston.

Ministry of Commerce, Trade and Industry (2011), Strategic Plan 2011 – 2015, Ministry of Commerce, Trade and industry, October

Mische, M.A. (2001), Strategic renewal. Becoming a high-performance organization, Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey.

Mittal, R. and Dorfman, P.W. (2012), ‘Servant leadership across cultures’, Journal of World Business, Vol. 47, 555–570.

Mwenda, A. and Mutoti, N. (2011), ‘Financial Sector Reforms, Bank Performance and Economic Growth: Evidence from Zambia’, African Development Review, Vol. 23, No. 1, 60–74.

Ngobo, P.V. and Fouda, M. (2012), ‘Is ‘good’ governance good for business? A cross-national analysis of firms in African countries’, Journal of World Business, Vol. 47, 435–449.

O’Reilly III, C.A. and Pfeffer, J. (2000), Hidden value. How great companies achieve extraordinary results with ordinary people, Harvard Business School Press, Boston.

Palrecha, R. 2009, ‘Leadership – universal or culturally-contingent – a multi-theory/multi-method test in China’, Academy of Management Proceedings, 1-6.

Plessis, S. Du and Plessis, S. Du (2006), ‘Explanations for Zambia’s economic decline, Development Southern Africa, Vol. 23, Issue 3, 351-369.

Quinn, R.E., O’Neill, R.M. and St. Clair, L. (ed) (2000), Pressing problems in modern organizations (that keep us up at night). Transforming agendas for research and practice, Amacom, New York.

Rees-Caldwell, K. and Pinnington, A.H. 2013, ‘National culture differences in project management: Comparing British and Arab project managers’ perceptions of different planning areas Palrecha, International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 31, Issue 2, 212-227.

Republic of Zambia (2006), Vision 2030: A prosperous middle-income nation by 2030, available at: http://unpan1.un.org/intradoc/groups/public/documents/cpsi/unpan040333.pdf, accessed; May 2, 2013.

Rousseau, D.M. and Fried, Y. (2001), ‘Location, location, location: contextualizing organizational research’, Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 22, 1-13.

Sirota, D., Mischkind, L.A. and Meltzer, M.I. (2005), The enthusiastic employee. How companies profit by giving workers what they want, Wharton School Publishing, Upper Saddle River.

Soest, C. von (2007), ‘Measuring the capability to raise revenue: process and output dimensions and their application to the Zambia Revenue Authority Palrecha, Public Administration And Development, Vol. 27, 353-365.

Stede, W.A. van der (2003), ‘The effect of national culture on management control and incentive system design in multi-business firms: evidence of intracorporate isomorphism’, European Accounting Review, Vol. 12, No. 2, 263-285.

Steiger, J.H. (2007), ‘Understanding the limitations of global fit assessment in structural equation modeling, Personality and Individual Differences Palrecha, Vol. 42, Issue 5, 893-98.

The Post (2013), Zambia’s poor work culture, editorial comment, December 17th, 36.

Underwood, J. (2004), What’s your corporate IQ? How the smartest companies learn, transform, lead, Dearborn Trade Publishing, Chicago.

Waal, A.A. de (2006, rev. 2010), The Characteristics of a High Performance Organization, Social Science Research Network, http://ssrn.com/abstract=931873, accessed May 1, 2013.

Waal, A.A. de (2012a), ‘Characteristics of high performance organizations’, Journal of Management Research, Vol. 4, No. 4, 39-71.

Waal, A.A. de (2012b), What makes a high performance organization, five validated factors of competitive advantage that apply worldwide, Global Professional Publishing, Enfield.

Waal, A. de and Chachage, B. (2011), ‘Applicability of the high-performance organization framework at an East African university: the case of Iringa University College Palrecha, International Journal of Emerging Markets, Vol. 6, No. 2, 148-167.

Wanasika, I., Howell, J.P., Littrell, R. and Dorfman, P. (2011), ‘Managerial leadership and culture in Sub-Saharan Africa Palrecha, Journal of World Business, Vol. 46, 234–241.

Wang, J. 2010, ‘Applying western organization development in China: lessons from a case of success Palrecha, Journal of European Industrial Training, Vol. 34, Issue 1, p54-69.

Weick, K.E. and Sutcliffe, K.M. (2001), Managing the unexpected. Assuring high performance in an age of complexity, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco.

Wu, J. (2013), ‘Marketing capabilities, institutional development, and the performance of emerging market firms: a multinational study Palrecha, International Journal of Research in Marketing, Vol. 30, Issue 1, 36-45.

Wu, J., Li, S. and Samsell, D. (2012), ‘Why some countries trade more, some trade less, some trade almost nothing: the effect of the governance environment on trade flows Palrecha, International Business Review, Vol. 21, 225–238.

Zagersek, H., Jaklic M. and Stough, S.J. (2004), ‘Comparing leadership practices between the United States, Nigeria, and Slovenia: does culture matter?’, International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, Vol. 11, No. 2, 16-34.

Zook, C. and Allen, J. (2001), Profit from the core. Growth strategy in an era of turbulence, Harvard Business Press, Boston.